"Equidistant" means the same distance (from the prefix "equi-", which means equal, and "distance"). Parallel lines are equidistant from each other. This means that every point on one line is always the same distance from the other line as every other point on that line.

It is important to remember here that when we are talking about "distance" in Euclidean geometry, we are referring to the shortest distance, and the shortest distance between a point and a line is the length of a perpendicular line from that point to the line.

Proving this is quite simple, using theorems we have already proven about parallel and perpendicular lines.

Problem

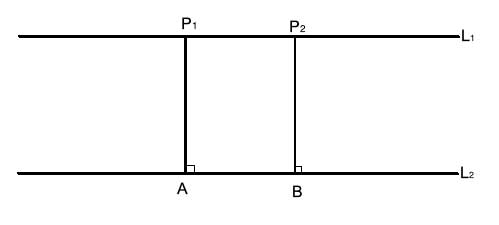

L1 and L2 are two parallel lines. Prove that these parallel lines are equidistant.

Strategy

Let's take a look at the diagram for this problem. The parallel lines and the two perpendicular lines that connect points P1 and P2 to line L2 form a quadrilateral. It certainly looks like that quadrilateral is a rectangle.

We know that in a rectangle, like in any parallelogram, the opposite sides are equal. So we'll proceed by proving that this quadrilateral is indeed a parallelogram. We will use the converse of the perpendicular transversal theorem - if a transversal line is perpendicular to two lines, then those two lines are parallel.

Proof

(1) L1 || L2 //Given

(2) P1A ⊥ L2 //Definition of distance

(3) P2B ⊥ L2 //Definition of distance

(4) P1A || P2B // (2) , (3), Converse of the perpendicular transversal theorem, L2 is perpendicular to both P1A and P2B

(5) P1ABP2 is a parallelogram //(1), (4), the definition of a parallelogram

(6) |P1A| =|P2B| //Opposite sides of a parallelogram are equal

Another way to solve this problem

In the section above, we used a little shortcut to show that the two lines (P1A, P2B) are equal. We relied on the fact that in a parallelogram opposite sides are equal. But what if we don't remember that property of parallelogram? Or what if we don't recognize the hint in the diagram to look for a parallelogram?

There's another way to show that the two lines have equal lengths, using the tried and true method of congruent triangles.

Second Strategy

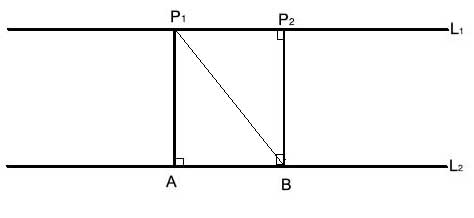

We'll create two triangles by drawing a line from P1 to B:

P1B is a common side in the two triangles, △P1BA and △BP1P2. L1 is parallel to L2, so by the alternating interior angle theorem, ∠BP1P2 ≅∠P1BA. P1A is perpendicular to L2, so m∠P1AB=90°. And also, P2B is perpendicular to L2, so m∠P2BA=90°.

But, using the consecutive interior angles theorem, we know that the sum of m∠P2BA and m∠BP2P1 is 180°, so m∠BP2P1 is also a right angle, and we can now show that △P1BA and △BP1P2 are congruent using the Angle-Angle-Side postulate, and |P1A| =|P2B| as corresponding sides in congruent triangles.

Proof (2)

(1) P1B =BP1 // Common side, reflexive property of equality

(2) L1 || L2 //Given

(3) ∠BP1P2 ≅∠P1BA //(2), alternating interior angle theorem

(4) P1A ⊥ L2 //Definition of distance

(5) m∠P1AB=90° //Defintion of perpendicular lines

(6) P2B ⊥ L2 //Definition of distance

(7) m∠P2BA=90° //Defintion of perpendicular lines

(8) m∠P2BA+m∠BP2P1=180° //(2), consecutive interior angles theorem

(9) m∠BP2P1 =90° //(7), (8)

(10) ∠P1AB≅∠BP2P1 //(9), (5) , defintion of congruent angles

(11) △P1BA ≅ △BP1P2 //Angle-Angle-Side

(12) |P1A| =|P2B| //Corresponding sides in congruent triangles. (CPCTC)